Thinking in Operators: Why Your Knowledge Base Should Be a Physics Engine

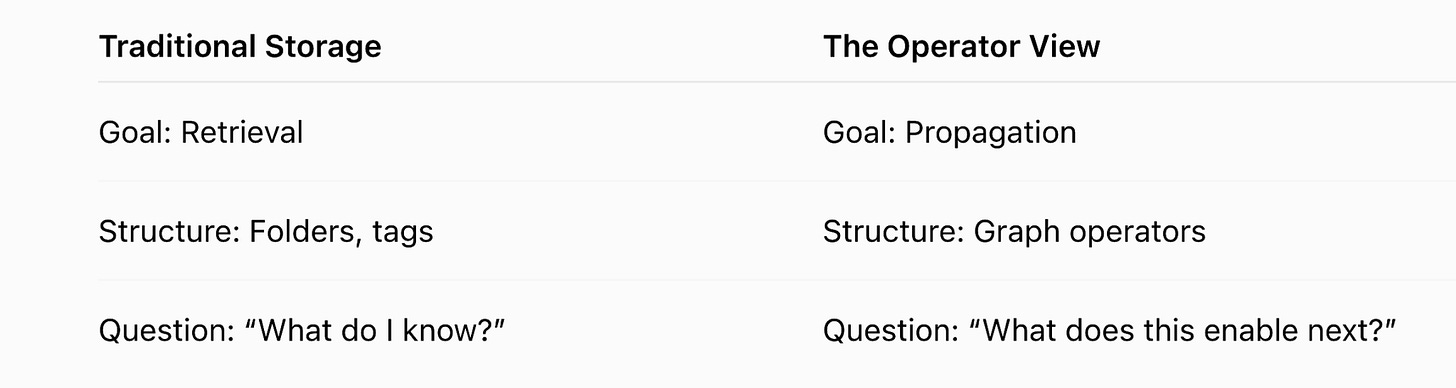

Most knowledge systems are built as storage. The real opportunity lies in movement.

We are taught to collect notes, bookmarks, and datasets like they are gold bars in a vault. Static facts feel valuable because they are scarce, but scarcity is no longer the problem. In a world of infinite data, storage has become cheap. What remains expensive is reasoning.

Static facts are just potential energy. They sit there, inert, waiting for something to happen. To unlock their value, we must turn them into kinetic intelligence.

The advantage today does not belong to the person with the biggest archive. It belongs to the person who builds the most efficient inference engine. When you represent knowledge as a graph, you stop merely having information and start executing it.

Beyond the Passive Map

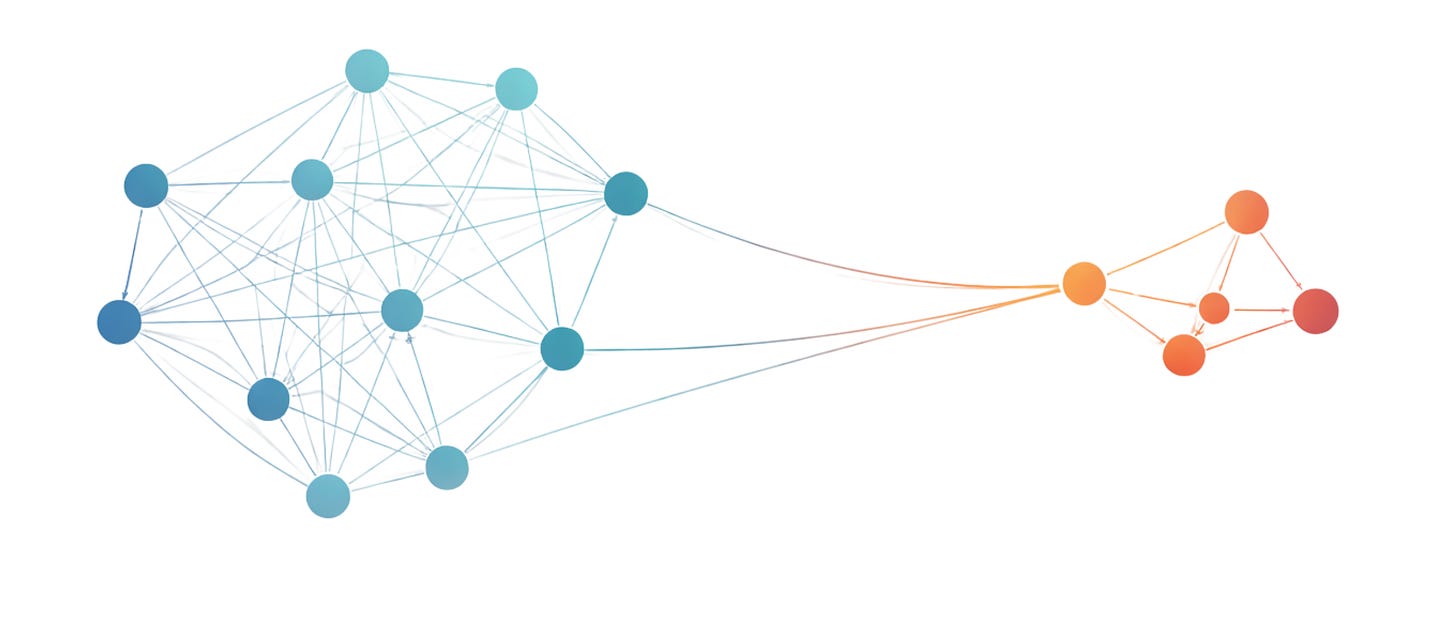

The passive graph is a map without a compass. You have likely seen them in the beautiful galaxy views of networked thought tools: nodes floating in space, connected by elegant lines. They are visually stunning and cognitively comforting, but they are also mostly static. Nothing ever happens when you look at them.

A graph becomes powerful only when you treat it as a dynamical system. In such a system, what matters is not just what you know, but how knowledge propagates, composes, and stabilizes over time.

This shift is subtle but decisive. You move from description to execution.

From Graphs to Operators

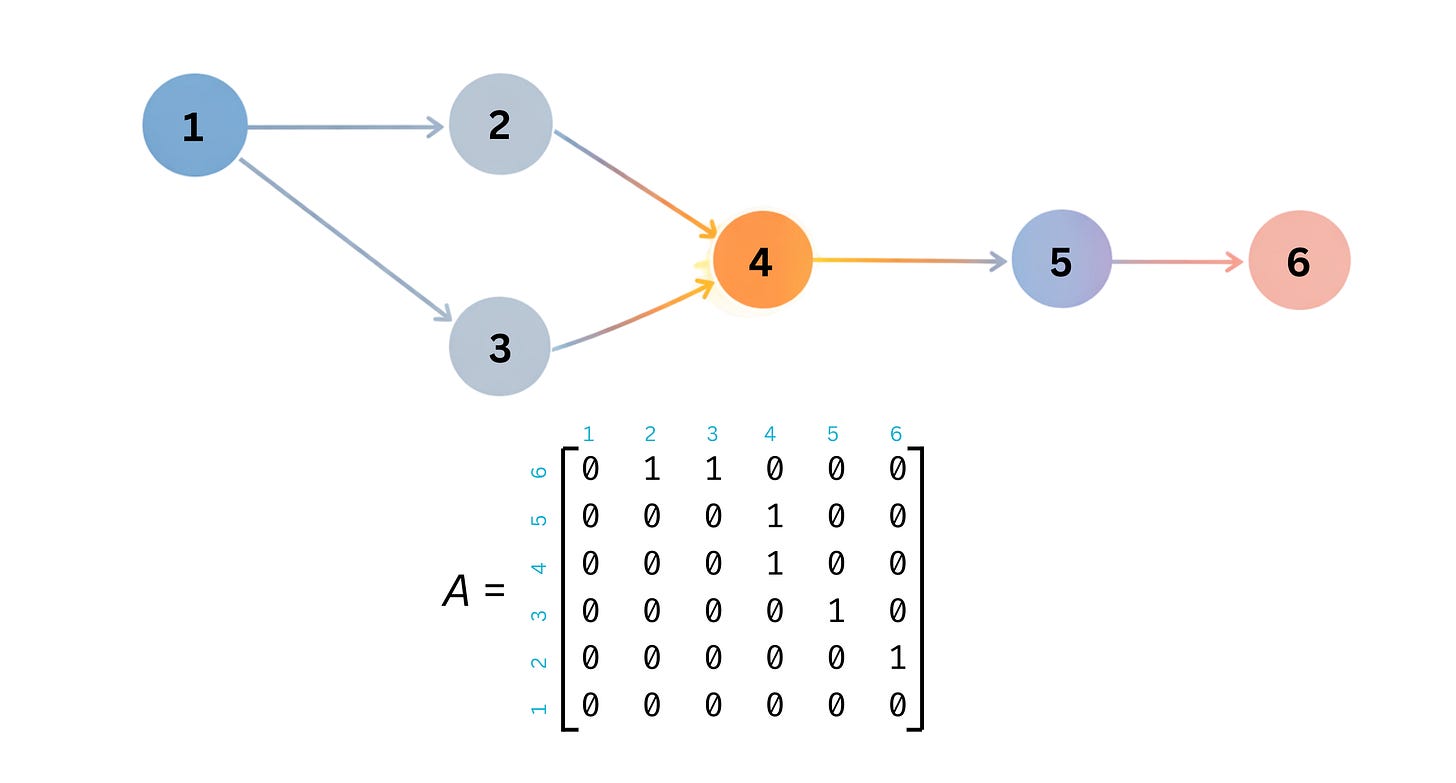

Imagine each node in your system is a concept, a claim, or a hypothesis. Each directed edge is not merely a similarity, but a justified implication: if this holds, that follows.

Once this graph exists, it can be written as an adjacency matrix A. Each entry A[i, j] encodes whether concept i enables, implies, or causally supports concept j. The exact interpretation depends on the domain, but the algebra remains the same.

At that point, the graph stops being a picture and becomes an operator.

Define a vector x as your current state of inquiry:

x[i] = 1 if concept i is active

x[i] = 0 otherwise

For simplicity, x is binary here, but the same framework works with continuous values representing confidence, probability, or strength of belief. This vector is not a list of facts; it is a snapshot of attention.

The smallest amount of math needed to make the idea precise is:

x(1) = A * x(0)

This single multiplication is a reasoning step. It propagates your current beliefs along valid edges, where validity is defined when the graph is built, whether by human judgment, learned models, or formal rules.

Apply the operator again and you reach second-order conclusions:

x(2) = A^2 * x(0)

In general:

x(k) = A^k * x(0)

Reasoning depth is matrix power. Inference is dynamics.

At this point you are no longer searching your knowledge base. You are letting it evolve.

Repeated application of the operator is not just deeper reasoning; it is a test of stability. As k increases, A^k reveals whether the structure converges to a stable configuration, oscillates under unresolved feedback, or explodes under unconstrained amplification. These behaviors are properties of the graph itself, not of any single fact. What controls this behavior is not any single node or edge, but the global structure of the graph. Certain patterns of activation reinforce themselves, while others fade away. These persistent patterns are the natural modes of the operator: directions in which propagation stabilizes, amplifies, or oscillates.

In linear algebra, these modes are captured by eigenvectors, and their tendency to grow or decay is measured by eigenvalues.

Application 1: Marketing Funnels as Causal Systems with Memory

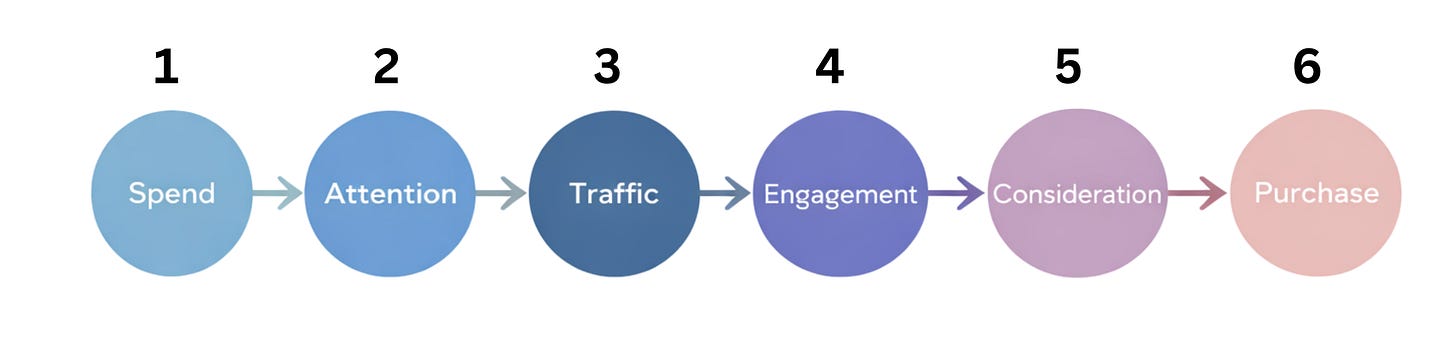

Marketing is often drawn as a funnel: spend leads to attention, attention drives traffic, traffic creates engagement, engagement leads to consideration, and consideration becomes purchase. Because this picture feels intuitive, the reasoning error hides in plain sight.

Define six discrete variables:

x1: media spend

x2: attention

x3: traffic

x4: engagement

x5: consideration

x6: purchase

The causal structure is a directed chain:

x1 → x2 → x3 → x4 → x5 → x6

For clarity, the funnel is drawn here as a simple acyclic chain, even though real systems often include feedback loops that make the dynamics even richer.

Most dashboards implicitly report P(x6 | x1), revenue as a function of spend. But this is correlation, not causation.

The quantity the business actually cares about is P(x6 | do(x1 = x1_tilde)), the effect of intervening on spend.

The do-operator distinguishes intervention from observation. Writing do(x1 = x1_tilde) means that x1 is set externally, cutting its incoming causes, and the system is allowed to evolve forward from this forced condition. Conditioning filters data; intervention rewrites the operator.

Written explicitly, the effect of intervention is a sum over internal trajectories:

P(x6 | do(x1)) =

sum over x2, x3, x4, x5 of

P(x6 | x5) *

P(x5 | x4) *

P(x4 | x3) *

P(x3 | x2) *

P(x2 | x1)

Each assignment (x2, x3, x4, x5) corresponds to one possible customer journey. Revenue is not produced directly by spend; it emerges as the weighted sum of all downstream paths.

This explains familiar pathologies. One campaign increases attention and traffic but degrades engagement. Another reduces reach but improves consideration. Both can generate the same short-term revenue while creating radically different long-term dynamics.

The failure of many attribution models is not statistical. It is dynamical.

Spend is not a lever. It is an initial condition in a system with memory.

A Necessary Detour: Why Causality Lives in Structure

This distinction between observing and intervening was formalized by Judea Pearl, one of the founders of modern causal inference and a long-time professor at UCLA.

Pearl’s key insight was deceptively simple: causation is not something you discover in the data. It is something you assert about the structure that generates the data. From this came causal graphs, do-operators, and a precise language for intervention.

It also explained why many systems that look sophisticated collapse the moment conditions change. They learn associations, not mechanisms.

Observation filters paths. Intervention rewrites the operator.

Application 2: Reliability as Structural Integrity

In a world shaped by deepfakes and synthetic media, we often try to evaluate information by inspecting content. This is a mistake. Content is easy to forge; topology is not.

Imagine a graph where nodes represent sources and claims, and edges encode support, citation, or dependency. Here, x represents the configuration of accepted or asserted claims in the network.

Reliability is not a label. It is a property of coherence.

Define a coherence energy:

E(x) = sum over i, j of A[i, j] * (x[i] - x[j])^2

Low energy corresponds to agreement across strongly connected parts of the network, while high energy signals tension. A claim that fits naturally into many independent paths of reasoning settles into a low-energy configuration; a claim that contradicts the structure forces strain.

We do not need to fact-check every node. We measure the inertia of the claim.

Truth is the configuration that requires the least tension to sustain.

Application 3: Matrix Multiplication as Discovery

A superpowered knowledge base does not wait for queries. It connects dots automatically.

Consider three simple statements:

x1, the material is crystalline;

x2, crystals have phonons;

x3, phonons scatter electrons.

Individually, none of these statements says anything about electron scattering in a crystalline material. That conclusion is not stored anywhere explicitly. It exists only as a potential chain in the structure.

This is exactly what the identity

(A²)[i, j] = sum over k of A[i, k] * A[k, j]

makes explicit.

Here, A[i, j] encodes a direct implication. For example, A[x1, x2] is nonzero because “material is crystalline” implies “crystals have phonons”, and A[x2, x3] is nonzero because “phonons scatter electrons”.

When we compute (A²)[x1, x3], the formula asks a precise question: is there an intermediate concept k such that c1 leads to k and k leads to c3? The answer is yes, with k = c2. The product A[c1, c2] * A[c2, c3] corresponds to the two-step reasoning path c1 → c2 → c3. Summing over k simply means checking all possible intermediate concepts.

In this sense, A² does not invent new knowledge. It reveals implications that were already latent in the graph. As higher powers of A are applied, the system explores longer chains of reasoning, making deeper conclusions accessible without ever writing them down explicitly.

Discovery, here, is not adding facts. It is allowing structure to unfold.

Why This Looks Like Physics

In physics, outcomes are computed by summing over all allowed histories, through a concept called path integral. This sum runs over discrete (or continuous) graph paths:

(A^L)[i, j] =

sum over k1, k2, ..., k(L-1) of

A[i, k1] * A[k1, k2] * ... * A[k(L-1), j]

Nodes are states of belief. Edges are allowed transitions. Matrix powers are histories of reasoning.

A knowledge graph defines a state space. An operator defines what can happen next. Not necessarily because the system obeys physical laws, but because the mathematics of constrained dynamics is the same.

Which dynamics will you allow your knowledge to execute today?

Your knowledge base does not have to be a library. It can be a laboratory. A library preserves the past, while a laboratory lets you intervene.

The future of high-performance thinking is not about collecting more facts. It is about designing better operators. When you stop asking how much you can store and start asking how much you can execute, you unlock a different level of cognitive agency.

First, this approach is oversimplified. Each action requires parameters, but may proceed with semantically various sets of objects. Depending on a situation, what is available to us may limit our options. Also we may vary the volume (we not only press the gas pedal, but decide how hard to press).

Second, using matrix multiplication may be inefficient in real time. Consider hierarchical fall through with logarithmic complexity.

Overall, I welcome this approach. Indeed, we need to store not only facts but also causal relations.